A team of scientists led by Oxford University have made a discovery that could improve our chances of developing an effective vaccine against Tuberculosis.The researchers have identified new biomarkers for Tuberculosis (TB) which have shown for the first time why immunity from the widely used Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is so variable. The biomarkers will also provide valuable clues to assess whether potential new vaccines could be effective.

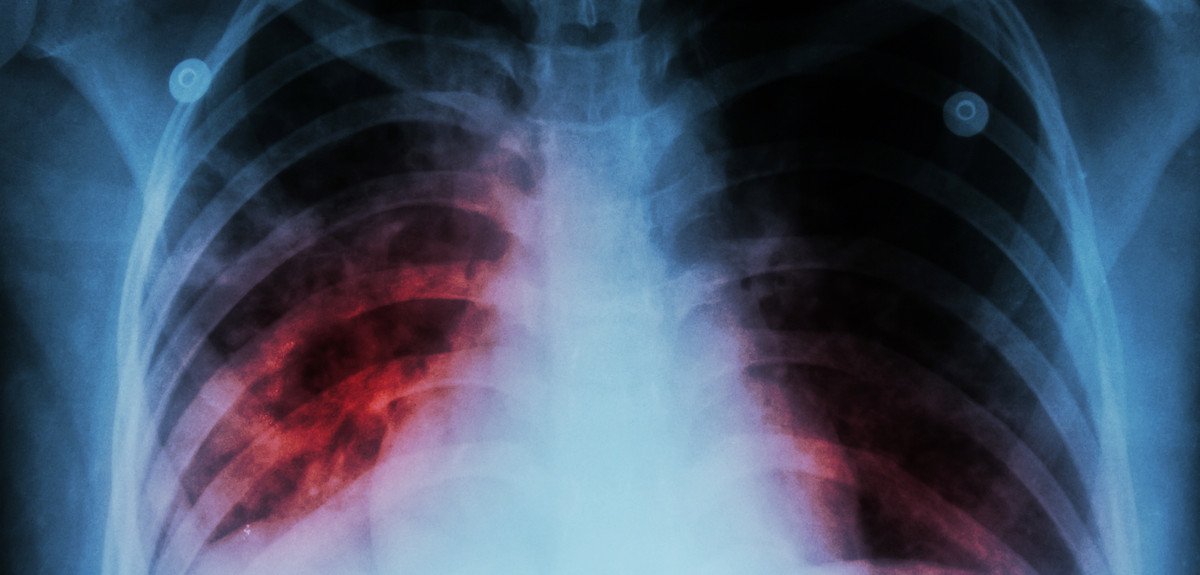

TB remains one of the world's major killer diseases, infecting 9.6 million people and killing 1.5 million in 2014. The only available vaccine, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), works well to prevent severe disease in children but is very variable in how well it protects against lung disease, particularly in countries where TB is most common.

While BCG is one of the safest and most widely used vaccines worldwide, there is one key issue: It is currently very difficult to determine whether it will work or not. This also makes it really hard to determine if any new vaccines might work.

For many vaccines, medics and scientists can use what are called immune correlates or biomarkers, typically in the blood, which can be measured to determine whether a vaccine has successfully induced immunity. Not only are these correlates useful in measuring the success of existing vaccination programmes, they are also invaluable in assessing whether potential new vaccines could be effective.

With a pressing need for a TB vaccine that is more effective than BCG, a research team drawn from a number of groups at Oxford University, working with colleagues from the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative at the University of Cape Town and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, set out to identify immune correlates that could facilitate TB vaccine development. The team, funded by the Wellcome Trust and Aeras, and led by Professor Helen McShane and Dr Helen Fletcher, studied immune responses in infants in South Africa who were taking part in a TB vaccine trial.

Professor McShane said: 'We looked at a number of factors that could be used as immune correlates, to try and find biomarkers that will help us develop a better vaccine.'

The team carried out tests for twenty-two possible factors. One – levels of activated HLA-DR+CD4+ T-cells – was linked to higher TB disease risk. Meanwhile, BCG-specific Interferon-gamma secreting T-cells indicated lower TB risk, with higher levels of these cells directly linked to greater reduction of the risk of TB.

Antibodies to a TB protein, Ag85A, were also identified as a possible correlate. Higher levels of Ag85A antibody were associated with lower TB risk. However, the team cautions that other environmental and disease factors could also cause Ag85A antibody levels to rise and so there may not be a direct link between the antibody and TB risk.

Professor McShane said: 'These are useful results which ideally would now be confirmed in further trials. They show that antigen-specific T cells are important in protection against TB, but that activated T cells increase the risk'.

Dr Helen Fletcher from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said: 'For the first time we have some evidence of how BCG might work, and also what could block it from working. Although there is still much work to do, these findings may bring us a step closer to developing a more effective vaccine for TB.'

Dr Tom Scriba from the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative said: 'TB is still a major international killer, and rates of TB disease in some areas of South Africa are among the highest in the world. These findings provide important clues about the type of immunity TB vaccines should elicit, and bring us closer to our vision, a world without TB.'

The team is continuing its work to develop a TB vaccine, aiming to protect more people from the disease.