Melioidosis, a difficult to diagnose deadly bacterial disease, is likely to be present in many more countries than previously thought, reports a paper published online today in the journal Nature Microbiology. The study predicts that melioidosis is present in 79 countries, including 34 that have never reported the disease.

It recommends that health workers and policy makers give melioidosis a higher priority, and expects the number of melioidosis cases to rise as diabetes increases across the tropics, especially among the poor, and international travel increases the risk of introducing the pathogen to new areas.

'Although melioidosis has been recognised for more than 100 years, awareness of it is still low, even among medical and laboratory staff in cionfirmed endemic areas,' said study co-author Dr. Direk Limmathurotsakul, Head of Microbiology at MORU and Assistant Professor at Mahidol University (Thailand).

'We predict that the burden of this disease us likely to increase in the future because the incidence of diabetes mellitus is increasing and the movements of people and animals could lead to the establishment of new endemic areas.'

The study is the first to provide an evidence-based estimate of the global extent of melioidosis, which is caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, a highly pathogenic bacterium commonly found in soil and water in South and Southeast Asia and northern Australia.

Led by researchers at Oxford University, the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit in Bangkok, Thailand, the University of Washington in Seattle and Mahidol University in Thailand, among others, the study is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

The highest melioidosis risk zones are in South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific including all countries in Southeast Asia and tropical Australia, Sub-Saharan Africa and South America, with risk zones of varying sizes in Central America, Southern Africa and the Middle East.

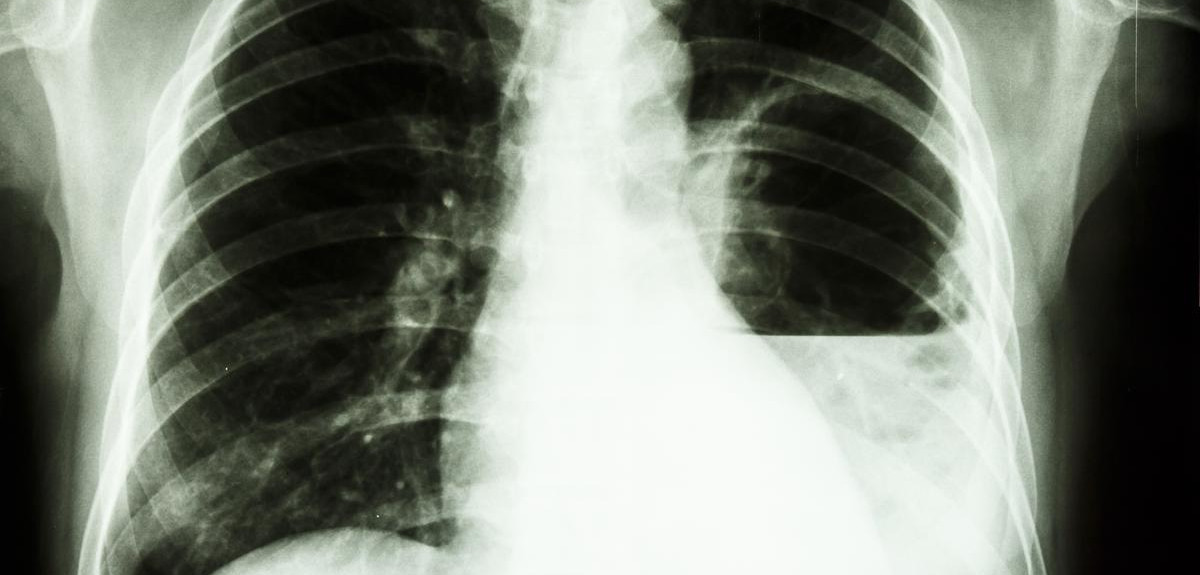

Contracted through the skin, lungs or by drinking contaminated water, melioidosis can be difficult to diagnose as it mimics other diseases. The bacterium is resistant to a wide range of antimicrobials, and inadequate treatment may result in fatality rates exceeding 70%.

'Melioidosis is a great mimicker of other diseases and you need a good microbiology laboratory for bacterial culture and identification to make an accurate diagnosis. It especially affects the rural poor in the tropics who often do not have access to microbiology labs, which means that it has been greatly under estimated as an important public health problem across the world,' said Dr. Limmathurotsakul.

'Our study predicts high infection rates in countries like India and Vietnam, where the disease is gradually being recognised more frequently.'

The study estimates that melioidosis killed 89,000 of the 165,000 people who got it in 2015 – nearly as many as the annual global mortality from measles (95,000 deaths per year) and greater than deaths from leptospirosis (50,000 per year) or dengue (12,500 per year), two current health priorities for many international health organizations.

High-risk melioidosis groups include patients with diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease or excessive alcohol intake. The authors mapped documented hu8man and animal melioidosis cases and environmental reports of B. pseudomallei published between 1910 and 2014. They combined these in a formal model that suggests that melioidosis is severely under-reported in most of the 45 countries where it is known to be endemic, and that it is probably endemic in another 34 countries that have never reported the disease.

The authors suggest these results highlight the need for this diseases to be given a higher priority by health workers, international health organisation and policy makers.

'We hope that this paper will help to raise awareness of the disease among all healthcare workers in endemic areas, as the disease can be treated if it is caught early enough,' said Oxford researcher Dr David Dance, one of the contributors to the report, who first highlighted the under-recognition of melioidosis 25 years ago and now studies infectious diseases including melioidosis at the Laos-Oxford-Mahosot-Wellcome Research Unit (LOMWRU) in Vientiane, Lao PDR.