Genetics researchers at the University of Oxford have used DNA to map the history of population movements in and around Europe. The technique may help historians to understand more about how over nearly three thousand years people across the continent have migrated, mingled and multiplied. Their results are published in the journal Current Biology.

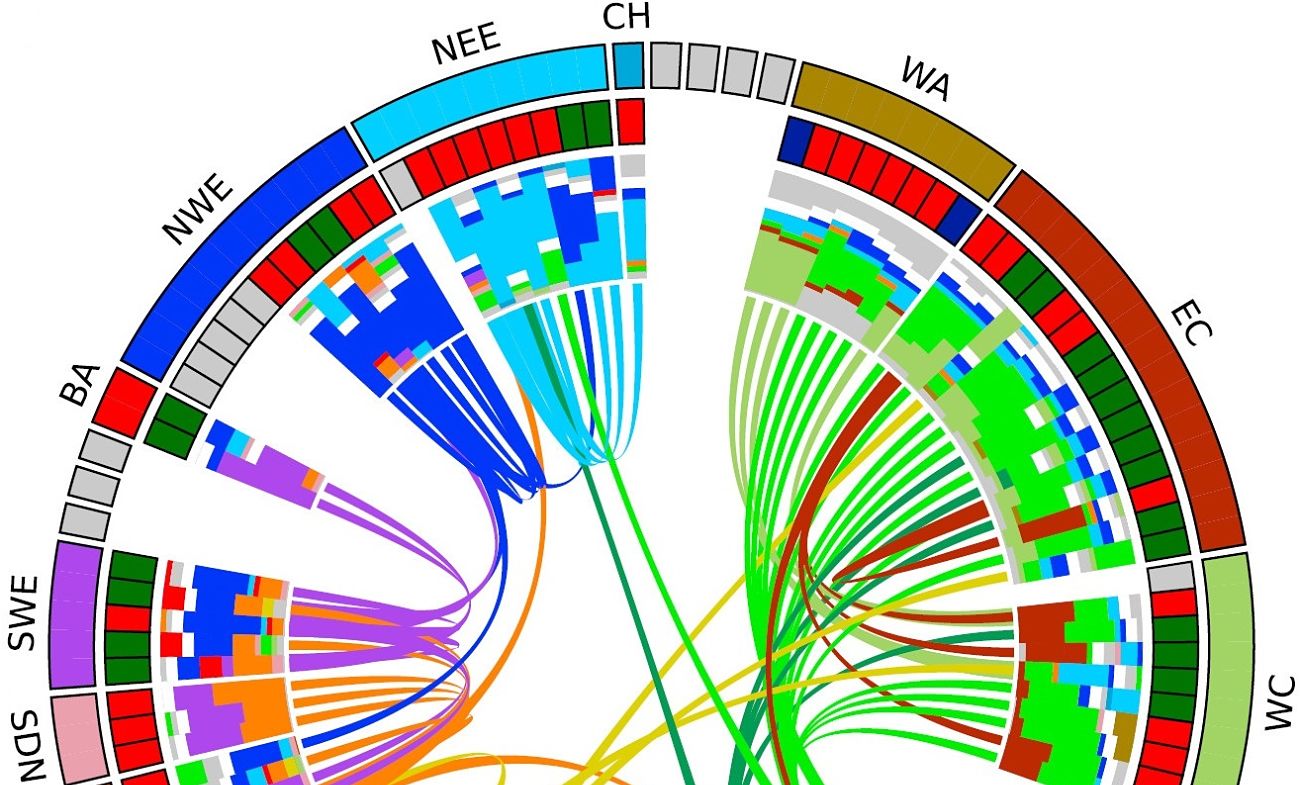

Studying 500,000 genetic markers in 2000 samples, the international team including the Department of Zoology and the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics and led by Prof Cristian Capelli, looked at how genes had been exchanged between 1000BCE and 1950. While half the samples were from within Western Eurasia (Europe, the Caucasus and areas of the Middle East), half were from other areas of the world, enabling the researchers to trace not only which groups moved around Europe, but also which groups migrated to the continent.

Dr George Busby, first author of the research, said: ‘We looked at admixtures, which is where you can see genes coming together with a minor source, the incoming group, and a major source, the settled group in the area. By looking at where and how individual genetic markers are found in the chromosome, we can piece together a genetic history.

‘As written historical records tend to be written by elites and winners, this technique can show what happened to ordinary people.’ Prof Cristian Capelli, senior author, added.

Using statistical techniques, the team were able to assign date ranges for when particular admixtures were happening. Unsurprisingly, some of those dates are well matched to items in the historical record. For example, genetic markers associated with Mongolian ancestry were dated to the time of Genghis Khan’s expansion.

However, other dates point to events that are not well known. Another period of Mongolian admixture was identified, revealing a population movement earlier than Genghis Khan, that was much less well known.

Similarly, those areas at the edge of Europe, notably around the Mediterranean have seen regular movements of African and Middle Eastern groups, followed by gene-exchange with Southern European populations.

Dr Busby adds: ‘These tools tell us something about the main population movements but they do not tell us that a particular individual is ‘x per cent Mongolian’ for example. Over time, across Europe, our genomes have become mosaics, as groups have mixed and remixed to form complex patterns of heritage that may include genetic markers from many different areas.

‘Because Europe has comprehensive written and archaeological records, we have been able to validate this technique by comparing our results to what is shown by those sources. What it tells us is that we could use the approach to understand more about the history of areas of the world where fewer records exist.’ Busby and Capelli said.

'It's clear that migration and admixture have been the norm, rather than the exception throughout human history,' they concluded